In 2015, if there was a ground zero for Europe’s migration crisis, it was here, on the western Turkish coast. But a few months on, a deal has been struck between the EU and Ankara which should see most migrants arriving in Greece being deported back to Turkey, and the picture is very different. The hotels are empty. And the shopkeepers on Fevzi Pasha Boulevard are largely back to their original stock.

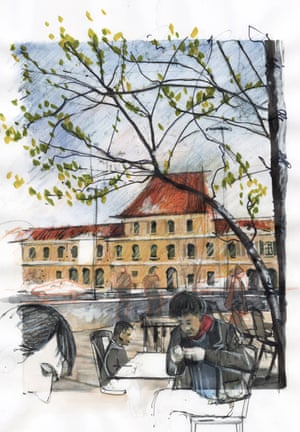

Sitting in a cafe in front of the train station, a thick orange scarf wrapped around his neck, a Syrian tailor watches people timidly as his son makes castles out of sugar cubes. A few weeks ago this cafe and the square teemed with smugglers conducting their illicit trade in the open, and refugees negotiating prices. Today, two Turkish police officers stand on a street corner to scare away smugglers and their clients.

The tailor and his son have been in Turkey for months, while their friends and relatives have reached Germany. But he cannot afford what the smugglers charge for a trip across the sea. Finally, after fidgeting with his scarf, his nails and his phone, he summons up the courage to ask a man sitting at the next table if he is Syrian.

Yes, answers the man. And you? “Yes, I am also Syrian,” the tailor whispers back. “I am a Kurd from Qamishli [a north-eastern city on the border with Turkey]. I want to go to Europe but I don’t have any money, so I am looking for someone to take me along. I will go like a servant, a friend, anything. I was a tailor in Qamishli and I can be very useful.”

But, he asks the man, how can he get to Europe if he does not even have enough money to buy bread for his five children? “Maybe in Europe I can find a job,” he wonders. “Do you know anyone who can help?” The man gives him a few lira to buy bread, and promises to help him find not a smuggler but a job.

No comments:

Post a Comment