The recapture of the Syrian desert city of Palmyra must lift the spirits of all who knew its former glory. But after the dust dies down, a new army arrives: that of archaeologists brandishing questions. How much of what has gone should be restored? By what means, and by whom? And where does Palmyra belong, to Syria or the world?

For once, there is no doubting the drive. Syria’s director of antiquities, Maamun Abdelkarim, is visiting Palmyra this week to survey the wreckage of his celebrated site, pleading for its rebuilding. His benefactor and Syria’s principal ally, Russia, has compared Palmyra’s restoration with that of Leningrad after the second world war. In Italy, the former culture minister Francesco Rutelli has ambitious plans to use digital “printing” to reconstruct Palmyra’s fallen temples from their rubble and dust.

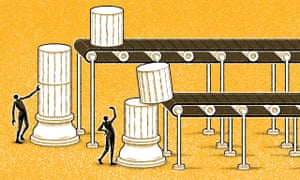

Private initiatives aren’t far behind. Oxford’s Institute for Digital Archaeology is the creation of American lawyer/archaeologist Roger Michel, with help from Harvard and Dubai. Michel is currently using similar technology to Rutelli’s – better, he claims – to build a 3D facsimile arch from Palmyra’s destroyed Temple of Bel. It is to be unveiled in London’s Trafalgar Square on 19 April and will then travel on to New York. “My intention,” declares Michel, “is to show Islamic State that anything they can blow up we can rebuild exactly as it was before, and rebuild it again and again. We will use technology to disempower Isis.” With the recapture of Palmyra all these ambitions must confront reality. The talk stops and something must happen. New 3D printing technology in particular opens a new front in the old argument among conservationists: between restoration and “conserve as found”, or between treating heritage as “done and dusted” as opposed to seeing it as an opportunity to discover new meaning, and new enjoyment, in the past.

Michel claims his printers can reproduce not just the texture and surface contour of stone but its physical make-up. They can extrude layers of the same sand, water and sodium bicarbonate that formed the artificial stone often used by the ancients. They can reconstitute the original dust of a ruin in situ. It is no different in concept from French archaeologists who, in the last century, re-erected Palmyra’s colonnade.

Meanwhile in a quarry in Carrara outside Rome, the decorative features of the Bel temple uprights are being etched by a CNC router-engraver. They are, says Michel, “completely indistinguishable from the original”. He is offering the Syrians two printers that, he claims, can operate at a speed that “should enable us to rebuild what has been destroyed inside six months”. Robotic artificial intelligence can be an aide to art as well as science. Michel is backed by London mayor Boris Johnson, an enthusiastic sponsor of the Trafalgar Square arch. Johnson demanded that “British archaeologists be in the forefront of the project”, especially given Britain’s “ineffective” role in failing to defend the site in the first place. David Cameron has yet to respond.

In Italy Rutelli’s 12 metre-high Big Delta printer is built by the Wasp Corporation and was first displayed at Rome’s Faire Maker digital fair last year. It has already been used to recreate portions of Pompeii and is being used to recreate the 4 metre-high winged bull of Nimrud in Iraq, smashed by Isis last year. While both Michel and Rutelli are handicapped by the lack of 3D scans of Palmyra, hundreds of photographs coupled with the new accessibility of the ruins should make amends.

No comments:

Post a Comment